Samarkand, Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan Past and Present

June 3, 2012

We've come to be the rules of your world

I am immortal, I have inside me blood of kings

I have no rival, No man can be my equal

Take me to the future of your world

Born to be kings, Princes of the universe

- Queen

After weeks of being in rather remote places seeing other tourists was something of a blessing. Then I arrived in Samarkand. In about three minutes here I had seen more tourists than I had in the last month of my travels. The busloads of tourists, both foreign and domestic, roll around town every day, and with good reason, there are some amazing things to see here.

Samarkand served as the capital of Tamerlane’s empire from the late 1300s and because of this it is dotted with numerous ancient madrassas, mosques, and mausoleums. Many of the buildings have been extensively renovated and restored with their modern facelifts leaving little traces of what they would have looked like after hundreds of years of weathering, wars, and earthquakes. Hopefully the restorations are at least accurate so that visitors gain an understanding of how this great capital city looked in its prime, although as I gather there are some disputes about this.

Whether it is true to form or not, the Registan is an amazing complex of three madrassas that occupies a central spot in the center of the old city. The large hulking entranceways to each richly tiled building are flanked by minarets and open to spacious courtyards, leaving the people walking in their midst to resemble tiny ants with cameras. Being a touristy place there is an entrance fee, for locals it is 600 Som while for foreigners it is 13,000 Som, an absurd markup. It is worth it though as behind each entrance gate there are detailed wood carvings, tile work, paintings, and of course souvenir shops. I hope the money goes towards further restoration work and not the low quality audio-visual light show at night that is run in a variety of languages over a heavy background hiss of audio noise.

Just to the north of the Registan is the Bibi-Khanym mosque and mausoleum, another large scale complex of buildings, the size of which is truly amazing considering the time period in which they were built. Some buildings in here have yet to be restored on the inside though they have been painted entirely white so there is nothing to see. In between the arrivals of tour groups the hollow high-ceilinged dome of the main building is a peaceful spot to sit as a few birds swoop in through the open doorways. Like almost every old building in the city the mausoleum opposite has its own admission and camera fee which compared to what you pay for the mosque hardly seems worth it.

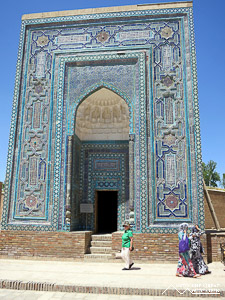

Further north, on a hill overlooking the Registan and Bibi-Khanym complex is the cemetery. The peculiar aspect of the cemetery is that the newer graves all have haunting engraved pictures of their occupants on the head stones, and they seem to stare directly at and through you as you walk by. They all share the same macabre style that leaves you with a chill and a sense of uneasiness that makes you walk just a touch faster. At the end of the cemetery is the Shah-I-Zinda, a long narrow walkway with dazzling mausoleums on either side. Here tourists from all over the world move elbow to elbow up and down steep staircases and narrow passageways through restored and un-restored mausoleums. The vivid artwork inside some of the mausoleums is stunning but the mid-day heat and crowds are sometimes too much to deal with.

After seeing so many ancient and historical buildings they all start to look the same, the entrance charges and camera charges also become an annoyance. But there was one final sight to see, the Gur-E-Amir mausoleum, which turned out to be one of the best. While not as amazing from the outside as the other larger buildings, this tomb of Tamerlane, his two sons, and two grandsons, is so dazzling on the inside that it more than makes up for it. In a small area a series of gravestones mark the location of the bodies and lie beneath a lofted ceiling supported by soaring walls that are spectacularly decorated with carvings, calligraphy, and colorful painting and artwork. The strangely narrow high arch on the side of the building only adds to the intrigue of the complex.

With such great numbers of tourists the infrastructure and surrounding area have been built up to take advantage of the tourists’ proclivity to spend money. Tacky souvenir shops and convenience stores in non-descript buildings line the wide pedestrian walkways around the main attractions. These new pristine buildings and walkways lend a character-less aura to the area and despite the grandeur of the ancient buildings it leaves you with a somewhat disappointing empty feeling.

This same feeling can be found at the centrally located Siob Bazaar, where you can see well stacked towers of dried fruits, nuts, and other vegetables in clean, well-organized, and sign-posted lanes. The chaotic and unique character of a bustling bazaar typical of Central Asia is nowhere to be seen here. It is as if the market was created solely for the tourists, that being said, the produce I bought was delicious and the food displays were eye catching.

In front of the entrance to the bazaar is where the money changers hang out. I know every country has its peculiarities but here in Uzbekistan, other than the extensive police presence, the currency is particularly perplexing and ridiculous. Uzbekistan has an official exchange rate for its currency, the Uzbek Som, which is set by the government and not determined by any type of free market. The current rate for that is something around 1800 Som for $1 US; I’m not sure exactly what it is because the number is mostly meaningless. The money changers that hang out at the bazaar all change money at the black market rates. The black market is only a black market in name as it operates quite openly, often in plain view of the police. The going black market rate is around 2800 Som for $1 US; a pretty significant difference. Now for the ridiculous part, the currency comes in four different notes: 100, 200, 500, and 1000 Som. If you do the math, the largest bill is worth about $0.35 US at the black market rates. This means that $100 US is 280,000 Uzbek Som, a big fat one and half inch thick stack of two hundred and eighty 1000 Som bills. Because of this wallets are almost impossible to use, save for holding credit cards and US currency, and you routinely see people handing over huge stacks of cash to pay for higher priced items. The novelty of this wears off quickly as you realize that you always have to wear pants with big enough pockets, or have some kind of a bag or backpack with you, in order to carry all your money, not to mention the need to count out so many bills when paying for things. The funniest part is that with their huge wads of cash and numerous gold crowns on their teeth from poor dental hygiene, many locals really do look like a stereotypical affluent gangster; and here in Central Asia they just might be.